Reporting Under Pressure in Cambodia

Cambodia’s media landscape has transformed dramatically over the past decade. What was once a competitive environment with independent outlets has become increasingly restricted. Beginning in 2017, the government launched a sustained crackdown on independent media ahead of the 2018 elections, forcing major outlets like the Cambodia Daily to close. According to Reporters Without Borders, this campaign has left most news outlets accessible to Cambodians under government control, with many topics now off-limits to journalists.

In this interview, Nop Vy, executive director of the Cambodia Journalists Alliance Association (CamboJA), discusses the state of press freedom since that pivotal 2017 crackdown. Today, only two or three truly independent local media outlets operate inside the country, even as approximately 2,000 registered outlets create an illusion of diversity.

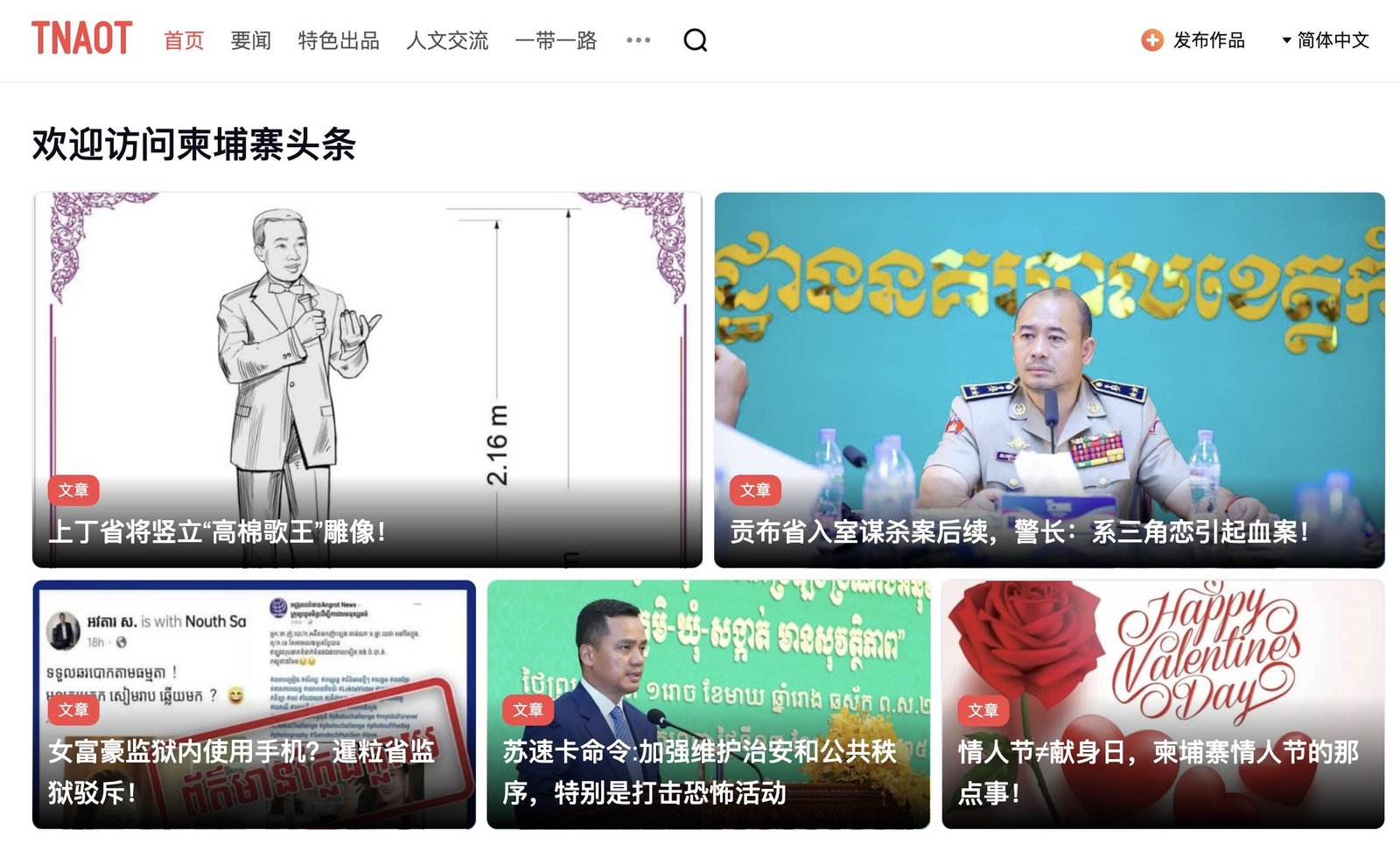

Vy also examines China’s expanding influence over Cambodia’s information environment. Through joint ventures, journalist training programs, and media cooperation agreements, Chinese state narratives have become deeply embedded in Cambodian media, shaping what information ordinary Cambodians can access and limiting balanced reporting on sensitive issues.

Speaking with Dalia Parete, Vy offers an insider’s perspective on the dangers facing journalists who cover corruption, politics, and land conflicts, while highlighting how Cambodian citizens themselves have begun to fill the void left by the disappearing independent media.

Dalia Parete: For people who are not very familiar with Cambodia, what does the media landscape look like, and how has it changed in the past decade?

Nop Vy: The real turning point came in 2017. That’s when the Cambodian government forced several independent outlets to shut down. The Cambodia Daily, an English-language publication, was forced to close over what authorities called “taxation issues” — but this was widely seen as a pretext to silence independent journalism. The Phnom Penh Post is still online today, but the print edition was shut down, and ownership transferred from an Australian to a Malaysian company with close ties to the prime minister’s family.

Around the same time, new outlets emerged that were closely aligned with the ruling party. Khmer Times, an English-language online publication, launched in 2014 and continues to operate today. Its owner has strong ties to the government. According to the Ministry of Information, there are around 2,000 media outlets operating in Cambodia. That sounds like a lot, but there is no real diversity in terms of editorial independence. Most outlets can’t freely cover political issues, social issues, or human rights. If you publish anything critical, you risk being forced to shut down.

DP: What happened to independent outlets?

NV: In 2023, we saw the only remaining local independent outlet, Voice of Democracy (VOD), forced to close its Phnom Penh operation. VOD was run by the Cambodian Center for Independent Media, an NGO, and now the former executive director operates it in exile from the United States.

So yes, there are many media outlets producing entertainment and breaking news. But there is nothing critical, nothing that gives people comprehensive information about what’s really happening.

For more on the press and China’s engagement in Cambodia, visit the Lingua Sinica country profile.

Today, I’d say there are only two or three truly independent local media outlets still operating inside the country. Our association, the Cambodia Journalists Alliance Association (CamboJA), runs one. We operate cambojanews.com, and this year we received the Anthony Lewis Journalism Prize Award from the World Justice Project for our work exposing online scam operations and human trafficking, and for promoting social justice.

Cambojanews focuses on investigative stories, human rights, and freedom of expression — though it has shifted more toward social issues, economics, and technology. That’s partly about survival. Independent media need to generate income somehow, and those topics are less politically risky.

DP: So when you say most newspapers are tied to the government in some way — what does that actually look like?

NV: Many function essentially as government mouthpieces. They simply reproduce and promote whatever the government says and does. They’re not producing stories that serve the public interest or affect people’s daily lives — stories about deforestation, illegal land grabbing, social justice issues, things that actually matter to local communities.

DP: You’ve been working in journalism for more than twenty years — as a reporter, an editor, and now as the executive director of CamboJA. What are your takeaways from these twenty years working in the press?

NV: Press freedom in Cambodia has moved backward compared to where we were before 2017. Back then, Cambodians had access to quality content from both Khmer and English-language newspapers. The media market was competitive — not in the number of outlets, but in the quality of content and investigative reporting. Journalists working for those outlets were deeply committed to the issues they covered and the scope of their stories.

People valued it. Even our former prime minister would read the Cambodia Daily every morning. He’d sometimes respond publicly to what he read. But after 2017, that quality disappeared. We became concerned about how people could access independent information that serves their interests and promotes social justice. What we’ve also learned is that even as independent media declines, citizens themselves have stepped up. They’ve learned how to do citizen reporting from their communities — providing firsthand information from the grassroots to journalists reporting at the national level.

DP: So it’s not just that they’re a source of information. They’ve actually taken on an active role in journalism production. Is that right?

NV: Exactly. As the social and political environment has become more restricted and civic space has shrunk, educated citizens have begun looking for ways to keep voicing their opinions and demand responses from policymakers. With more and more citizens online, they’re using these platforms to speak out. At first, it was just social — posting photos, that kind of thing. But over time, they started highlighting issues from their communities.

In some cases, people have actually influenced their local governments through social media to respond to problems. We have several case studies where citizens successfully influenced policymakers through the content they published online.

DP: You mentioned that most outlets can’t freely cover certain issues. For the journalists who do try to report independently, what are the most dangerous topics to cover?

NV: Last year, one of our partners conducted a study that identified the subjects journalists are most concerned about — topics where covering them puts their safety at risk.

The first is corruption, which is exposed by international media that is deeply connected to some powerful people in the government.

The second is politics. In 2017, the Supreme Court dissolved the main opposition party, the Cambodian National Rescue Party. This created enormous political conflict. More than 100 former politicians now live in exile — in France, the US, Australia, and elsewhere. They continue to challenge the current government, which has made political reporting incredibly sensitive.

The third subject is land conflicts. The government had granted millions of hectares through economic land concessions, affecting hundreds of thousands of families across the country. This has sparked numerous protests against private companies and authorities.

When journalists report on these issues, they face real risks. Even today, environmental journalists reporting from remote areas face legal action from local authorities and private companies.

Just last December, an environmental journalist reporting in Siem Reap province — where Angkor Wat is located — was shot dead by gangsters. Land issues, deforestation, and land grabbing are all dangerous issues. Some journalists have been threatened. Some have been physically attacked.

DP: Now, let’s shift toward China. Cambodia and China have had a long relationship that’s grown stronger over the years, with many cooperation agreements between Cambodian outlets and Chinese state media. What does this relationship look like in practice? Are you seeing Chinese content appearing in Cambodian media, or narratives from China being echoed?

NV: From my observation, the Chinese government plays an active role and extends its influence through different actors — not just through direct government channels, but through collaboration with Cambodian tycoons who, like Kith Meng, operate major media outlets. Meng operates three large television stations in Cambodia. These stations never amplified the voices of vulnerable people — especially those affected by the hydroelectric dam he operates with Chinese and Vietnamese companies. This is one way China extends its power and influence: through business sector collaboration.

NICE TV operates as a joint venture between Cambodia’s Ministry of Interior and Chinese investors. The station was initially announced in 2015 with backing from China Fujian Zhongya Culture Media Company (福建中次文化傳媒有限公司). However, by its 2017 launch, the Chinese partner was identified as NICE Culture Investment Group from Guangxi.

DP: With our platform, Lingua Sinica, we’ve tracked at least 33 partnerships between Chinese and Cambodian media — mostly Xinhua and other Chinese state outlets. But you’re describing something different: Chinese companies that do business in Cambodia but also push media content.

NV: Yes. And it goes even further. The government has also granted radio licenses to Chinese companies to operate local stations that broadcast in both Chinese and Khmer.

There’s also the Cambodia-China Journalists Association, which is co-chaired by Cambodian and Chinese journalists. Through this association and other channels, the Chinese government provides many opportunities to Cambodian journalists — training programs, conferences, and sponsored trips to China. Chinese government narratives get channeled into the region this way. Regional journalists are constantly invited to cover events in China and to speak at summits as prominent figures.

DP: We’ve traced a lot of Chinese-language media in Cambodia. Can you tell me about domestic Chinese-language media there? Do you think they’re serving the Chinese diaspora community?

NV: That’s a good question, but honestly, we have very little information about these Chinese-language media companies — especially their influence on the Chinese community in the country.

What I can tell you is that the Chinese and Cambodian governments have been working together on media capacity building. The Ministry of Information has partnered with China to train local journalists and provide technical assistance on digital infrastructure. This is another form of influence.

According to studies by Taiwan’s Doublethink Lab, Chinese influence in Cambodia operates through four channels: politics, foreign affairs, media, and economics. Media is a significant part of this influence. But regarding the Chinese-language outlets specifically, local organizations and researchers have been largely silent about their practices and impact.

DP: When you look at the Chinese presence in Cambodia, all the cooperation agreements and training programs, what does it mean for the information environment that ordinary Cambodians are getting? Is there any possibility for them to access balanced information on China?

NV: Because so many journalists are invited to attend and report on Chinese events — often through associations that promote Cambodia-China trade — that content dominates the information landscape.

The situation is made worse by the lack of independent media. Independent outlets play a critical role by producing content that offers different perspectives and analysis. Cambodian journalists used to scrutinize both the government and Chinese investment. They would point out that while China invests heavily in infrastructure, the quality often isn’t very good, whereas Japanese investment in Cambodia tends to be more sustained and higher quality.

Now there’s a lot of one-sided content favorable to China.

As for finding balanced information, this is a major challenge. The information landscape is dominated by narratives shaped by Chinese influence in Cambodian politics. Even academic institutions receive funding from China, which affects the research they conduct. When you try to find information about China’s influence in Cambodia or issues like Taiwan, it’s very difficult to find balanced reporting.

Nop Vy is a Cambodian journalist, advocate and the current Executive Director of the Cambodian Journalists Alliance Association (CamboJA).