Flickering Flames

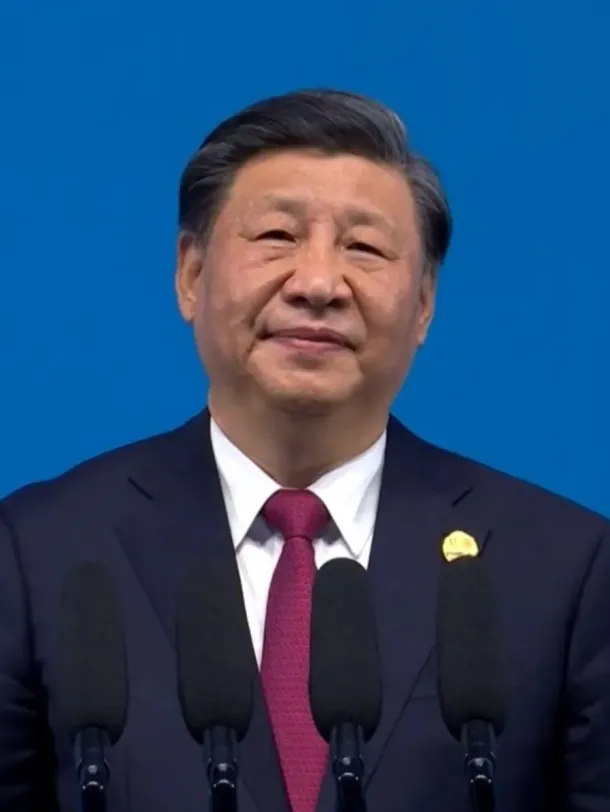

Two decades ago, as China’s civil society expanded amid the rise of the internet, and the country’s lawyer system privatized, a distinctive group of human rights lawyers (人權律師) emerged to challenge the legal system through individual cases. From the 2003 “citizen rights awakening year” (公民維權元年) through landmark cases like the Qing’an shooting incident (慶安事件), in which an unarmed man was shot by a police officer in Heilongjiang province, lawyers like Xie Yanyi (謝燕益), Wang Yu (王宇), Pu Zhiqiang (浦志強), and Li Heping (李和平) used constitutional arguments (and sometimes savvy dealings with the press and internet) to defend marginalized groups — pushing the boundaries of legal advocacy in an increasingly open public sphere. In 2005, Hong Kong newsmagazine Yazhou Zhoukan (亞洲週刊) chose Chinese human rights lawyers as its Person of the Year.

The 2015 “709 Crackdown” (709大抓捕) marked a devastating turning point. Beginning July 9 that year, authorities detained over 300 lawyers and activists nationwide, effectively dismantling China’s civil society. Ten years later, many remain imprisoned, disbarred, or under surveillance. They are the subject this month of a superb retrospective series by the online outlet WOMEN (我们). While some lawyers continue working under severe restrictions and others have fled abroad, the vibrant era of collaborative rights defense (維權) has ended, leaving behind scattered individuals maintaining what one lawyer cited in the report calls “the flickering flames of rule of law” (法治火種).