After the Layoffs

By Hsu Chia-Chi | Edited by Jordyn Haime

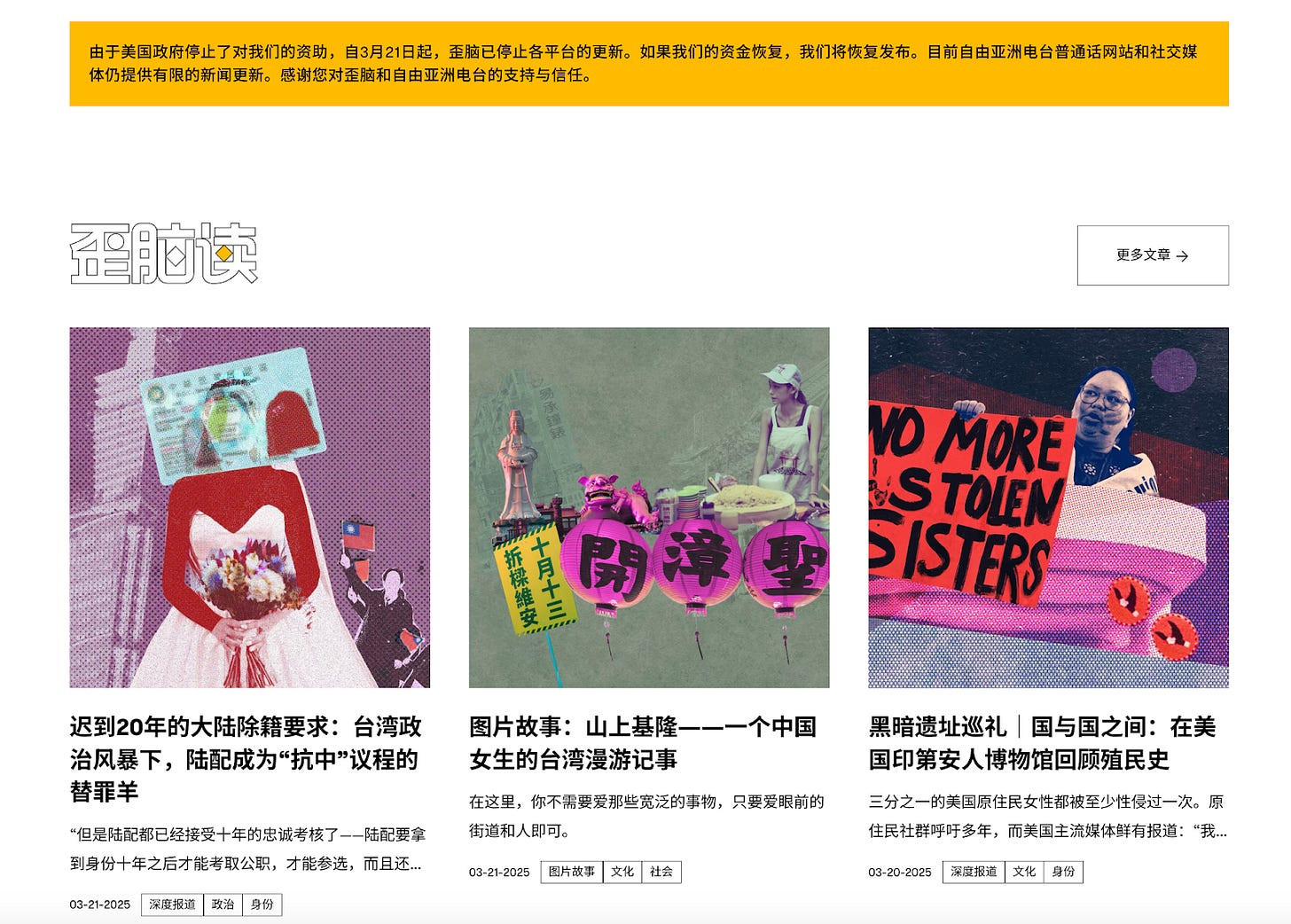

Liu I-lo remained buried in journalism work, even on the eve of being informed of the layoffs at WHYNOT, or Wainao (歪脑), the Chinese-language platform launched in 2017 under the US-run Radio Free Asia (RFA) news service.

“In our final breath, we rushed to get a lot of articles out, publishing what we could. In the last two weeks, we hurried to process all contributor payments, kept phone numbers active so writers could continue receiving payments — and we made our best effort to ensure we compensated for unpublished pieces,” he recalls. “We self-funded our SOPA submissions to completion,” he added, referring to the prizes for journalism excellence given each year by the Society of Publishers in Asia.”Even in the worst-case scenario that we were completely destroyed in the end, there were awards to win. What’s more, we did our job well, whether keeping pace or speeding things along.”

Liu was not alone. For many journalists at RFA and Voice of America (VOA), the last few months have been particularly difficult. It hasn’t just been about losing journalism jobs, but about the journalistic values they were able to practice at these outlets — and facing the possibility of having no real place to exercise those values again, or even lacking the capacity altogether.

Beginning in March 2025, the funding for multiple media outlets under the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM) – the independent U.S. agency that has funded media broadcasters like RFA and Voice of America (VOA) — was abruptly frozen. VOA, which primarily broadcast to East Asia, laid off nearly 100 people, while RFA underwent massive layoffs, with most staff placed on unpaid leave without work authorization. As of August, only 81 employees worldwide remained employed, with most programs suspended.

For this article, we spoke with multiple journalists who worked in various departments and positions at RFA. They discussed how they faced the sudden news of dismissal and how they have contemplated concerns about the future since, from the perspective of their personal lives as well as their journalistic values. Given ongoing professional considerations, the three sources agreed with Tian Jian to speak anonymously. They are identified here as Chen Mai, Jhou Sin, and Liu I-lo.

Project Layoff

In late November 2024, just after Donald Trump was elected to the presidency, USAGM internal staff were all discussing “Project 2025,” a policy blueprint prepared by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative American think tank. An entire chapter in this 900-plus-page document discussed the “reform” of public media, including USAGM’s overseas broadcasting.

Jhou Sin, a former employee of RFA’s Cantonese service, said in an interview that employees knew as early as late 2024 that there would be personnel reform after the election. No one expected mass layoffs.

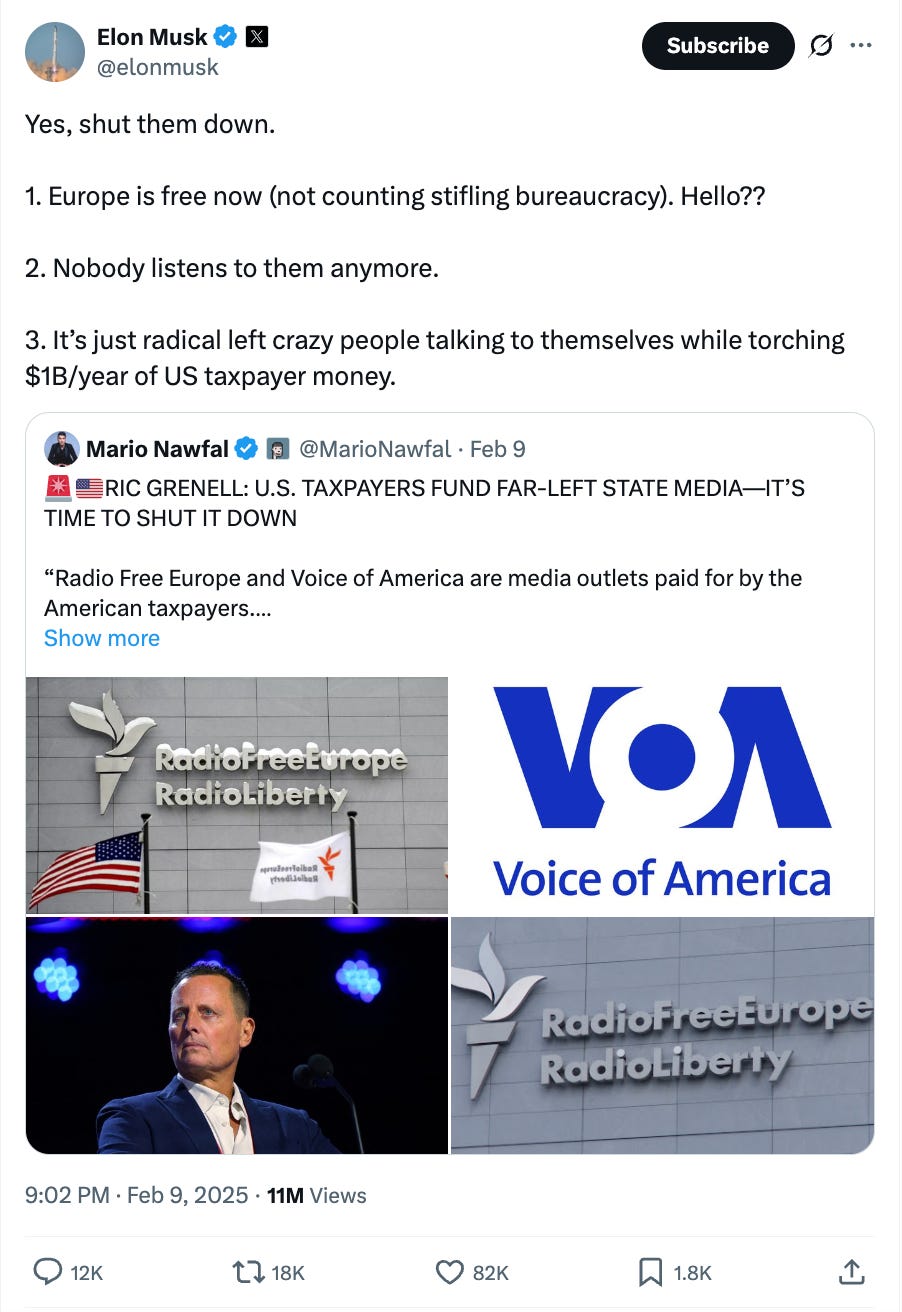

“We vaguely knew Trump would ‘reform’ us after taking office, but we didn’t know what methods would be used. Everyone could only guess, thinking that VOA and RFA might merge, or that the Mandarin and Cantonese services might combine,” said Jhou. But soon after, Elon Musk, then head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), criticized USAGM on X. Shortly after, DOGE took over USAGM, and waves of budget freezes, unpaid leave, and batch layoffs followed.

Liu I-lo’s recollection is similar to Jhou Sin’s. At the time, the company made employee retention decisions based on various labor laws and visa statuses in different locations and bureaus, trying to maximize protection of employee interests. Each individual’s situation was different, but with operating funds shrinking by the day, there was no other choice but to make increasingly poor decisions.

“Most DC colleagues were furloughed, overseas staff at the time didn’t know what would happen, contractors had their contracts immediately terminated, our part-time colleagues were suspended one after another, colleagues in the UK and Canada were also laid off, followed by major layoffs at the Taipei office,” Liu recalls.

“This is what being a journalist is. Even if the sky falls, you have to do reporting.”

During those months, Liu said, although RFA was still operating, management became increasingly sensitive about certain types of content.

“When we saw news about USAID being heavily targeted, everyone already knew we shared the same vulnerabilities,” said Liu. “Those non-profits funded by USAID — we initially tried to report on them. But these pitches were rejected by upper management. Because you knew you would be next. So actually many ideas in the editorial department were rejected by upper management.”

Other topics of concern to target audiences, including human rights, gender, and geopolitics, were also often softly rejected by senior management. As ideological lines became clear, many articles and videos already published were “temporarily removed,” as management explained. For other topics in planning or already in progress the phrase was “publication postponed.” Liu recalls that during that time almost every weekly editorial meeting involved trying different approaches to softly resist — this being a tactic generally associated with more repressive environments like that in Hong Kong.

“You have to think, USAID has humanitarian crisis-level funding under it. If [the U.S. government] doesn’t even care about that, why would it care about small-scale matters like ours?” Liu said.

Subsequently, waves of unpaid leave and batch layoffs began. Liu I-lo recalls that after colleagues were informed of layoffs, they were constantly busy with various forms of administrative cleanup. “This is also what being a journalist is,” he said. “Even if the sky falls, you still have to do reporting. Suppose the Earth is going to explode tomorrow, would you do a report today?”

On March 22, WHYNOT was the first outlet within the agency to shut down. On social media, they published a farewell message: “WHYNOT’s website and social media will stop updating on March 22 and 24, respectively; the website and social media can continue to be viewed normally until further notice. We look forward to reuniting with all WHYNOT readers when the skies clear after the rain.”

The Cantonese service, where Jhou worked, announced its closure on June 30 and stopped updating on July 1.

“I feel I have already earned three months more than others, not earning money, but earning time,” Jhou said. “Being pessimistic, I knew I would definitely be laid off; it was just a matter of time. At first, I felt confused, but later I gradually adjusted to doing whatever I could. We wanted to be the last group to close the door, and if it really had to end, then we wanted to end it decently.”

RFA was formally established in March 1996, its mission to “broadcast news and information to listeners in Asia who are otherwise denied access to full and free information.” This was nearly seven years after the Tiananmen Square massacre, which had ushered in a period of renewed press control in China — even as the economy was expanding and the Internet revolution just around the corner.

The Cantonese service of RFA was established two years later, in 1998, soon after the transfer of Hong Kong’s sovereignty to the PRC under the “one country, two systems” formula. Protections for press freedom in the territory continued to make it an ideal space for local language journalism that could be broadcast across the region, even reaching audiences across the border in Guangdong.

The situation changed dramatically with the passage of Hong Kong’s National Security Law in 2020. As many local journalists from such media as Apple Daily and Ming Pao were purged by the Hong Kong authorities, RFA’s Cantonese service became an increasingly popular source of news for Hong Kong people.

“With the anti-extradition movement, the National Security Law, and the departure of [journalism] colleagues from Hong Kong, the Cantonese service has experienced a lot of turbulence in recent years,” said Jhou. “But even under so much turbulence, everyone still produced strong reports.”

Yielding to China

Chen Mai worked as a designer at RFA and was also laid off in May 2025. Born in Hong Kong and currently living in Washington, D.C., he has already started looking for a new job.

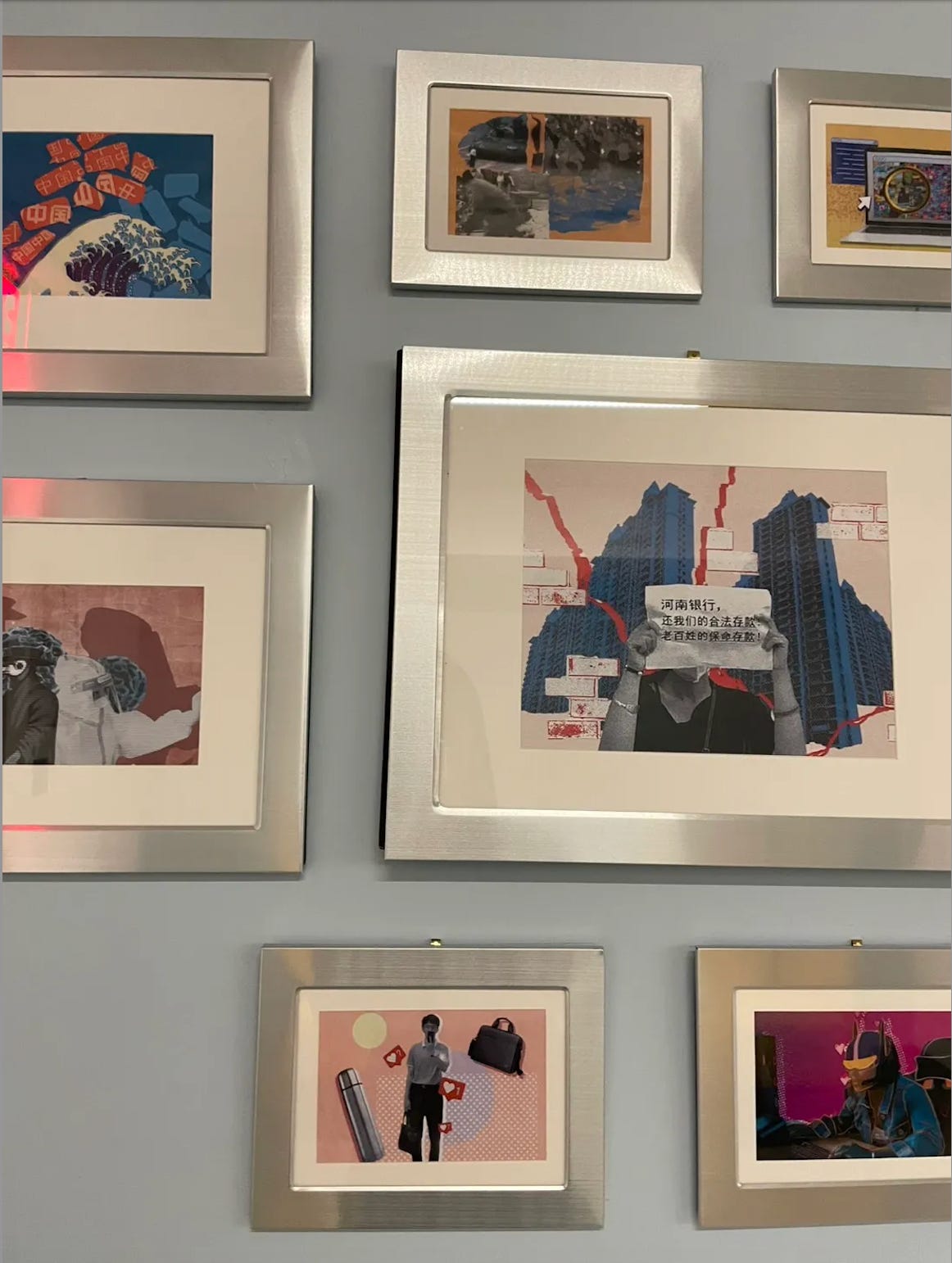

Chen joined RFA in 2019 and contributed to many major digital feature productions, including several award-winning reports.

“Coming to RFA was quite important for me at the time. The feeling then was, ‘we can make something important,’ which somewhat alleviated my political depression,” said Chen, referring to his emotions around the direction of Hong Kong.

Having come to America just a few years ago and now facing layoffs, he still believes he ultimately had to leave Hong Kong. What is more difficult is seeing other colleagues who are stuck due to issues with their immigration status.

Chen added that RFA has multiple language services, including Cantonese, Tibetan, and Uyghur services, and that “those in the most difficult situations are employees who have worked for years in these small language services.” Not only do they face issues with their visa status, but it is also difficult for them to find new jobs in the short term, with some still hoping the outlet might restart operations.

There has been no sign that will happen — even as many argue that the loss of the services is to the detriment of press freedom globally.

After RFA stopped receiving funding in March, CEO Bay Fang said: “The termination of RFA’s grant is a reward to dictators and despots, including the Chinese Communist Party, who would like nothing better than to have their influence go unchecked in the information space.”

Former US Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, a former MSNBC commentator and Washington Post columnist, similarly described the cuts as “giant gifts to China,” with people in Hong Kong, Tibet, Xinjiang, and elsewhere now receiving a diminishing volume of information about human rights from outside sources.

Jhou Sin believes the US government certainly has its own considerations in terms of RFA and VOA content and its goals, but at the very least, USAGM regulations guaranteed editorial independence and editorial oversight, which meant substantial resources going to media that had a duty to professional reporting. “In comparison, other diaspora media don’t have such resources,” said Jhou. “Thirty minutes of daily programming, lots of features and commentary, and a high-frequency of updates on social media.” These had an appreciable impact on the news environment in Hong Kong, he believes, and he said he could foresee that after the end of RFA, the flow of news in Hong Kong could decrease significantly.

“Bay [Fang] was right, this is the biggest gift to the CCP. With the end of the Cantonese service, I also believe Hong Kong’s pro-government media may increase their propaganda efforts,” Jhou said.

Of course, many in the region have also criticized journalists working at RFA and VOA for taking US government money and producing what they deem to be propaganda for “foreign hostile forces” — a phrase China has long used to broadbrush critics as conspirators.

“This matter itself is quite strange,” Liu said in response to those criticisms. “If I could write my reports without constraint in China and Hong Kong today, would I still need to go [to RFA]?”

“Critics will say that everyone is just issuing American meal tickets, thinking they’re doing good deeds, but under the entire world system as led to date by America, these articles are nothing more than cups of water trying to put out a burning cart of firewood,” said Liu, referring to efforts by Western-funded Chinese-language media organizations to fill the void left by the collapse of independent journalism in China. “For me, there’s nothing particularly special about this so-called [criticism]. It’s just whether a piece of reporting can be done well, whether there’s sufficient space to do it. Because Chinese-language media is now in a state of collapse, but if it can stir up even a small ripple, then it’s worth doing.”

Continuing Resistance

After his work at RFA ended, Liu interviewed everywhere — mainly for visa reasons. He didn’t limit himself to journalism, applying for jobs at convenience stores, sushi restaurants, and retail shops, and for restaurant server and sales representative positions.

No more journalism? He admitted that a senior Chinese-language journalist and editor’s resume is completely useless where he currently lives.

“I was targeted by the government before; now I’m being targeted by the government again.”

“When I looked for work, asking where they needed servers, saying I could speak Chinese and English, and Cantonese too, they said ‘very good, very good,’ but they didn’t have time to train me and needed someone with experience. This is a vicious cycle — how can I gain experience if I need it to land a job in the first place?”

He started by calling a local Chinese-owned sushi restaurant. “The boss was from Fuzhou and immediately said a lot of discouraging things — babbling on about how the hours here are long, no one will teach you — and then had me start helping in the kitchen. The boss was indeed willing to teach me: cutting avocados, cutting mangoes, peeling the thin skin off imitation crab. I worked this job for a few days. Then one day, I got the time wrong and was fired immediately.”

Following this experience, Liu edited his resume, removing the content about his past roles as a “senior journalist” and replacing it with restaurant kitchen experience.

“The funniest thing was, I used my previous journalist resume to apply for a staff position at a store, asking if it could be passed to the manager. There was no reply. Later, after editing a new resume, I saw that store again, applied again, and this time got an immediate reply.”

For now, Jhou Sin doesn’t need to worry about visa issues. But his life has descended into a state of confusion — as he finds it difficult to engage with issues around him.

“Before, I spent so much time every day desperately thinking of story ideas, proactively reading different news sources,” he said. “Now I have no motivation left. I wake up and barely read the news, just casually browse, because there’s no goal to aspire to. Why come up with story ideas anymore? So instead I feel somewhat empty.”

This is not the first time Jhou has experienced unemployment. The first time was when he was working for local media in Hong Kong.

“I was targeted by the government before; now I’m being targeted by the government again,” Jhou said. “The first time I lost my job, I thought I didn’t want to work in this profession anymore. That sense of powerlessness was strong. But at that time, my current supervisor used his silver tongue to convince me to come work here [at RFA]. It wasn’t easy then to pick up my enthusiasm for journalism again, and now once again it has to end. That old sense of powerlessness has returned.”

Chen Mai is job hunting now, too. Compared to other American cities, Washington, D.C. has more severe unemployment issues due to massive layoffs across government agencies. He is contemplating whether he should change fields or continue to work in the media.

The experience has served as a reminder not to self-censor due to political pressure.

“My point is that we absolutely cannot censor ourselves, cannot modify content according to readers’ preferences or interviewees’ partiality, and cannot self-censor because of pressure from above,” Chen said. “I experienced all of this at RFA, but even if you are subject to political censorship, you cannot rationalize this. You need to resist. You need at least to debate.”

“Once we become submissive, thinking that [accomodation] can protect us, we still get targeted in the end,” Chen added. “And being targeted has nothing to do with content actually having an issue. All these compromises are irrational and will only make you less like a news organization.”

Regarding journalism work, Liu I-lo stands by his professional record. “I’m confident that everything that came from my hands was professional work. I never considered RFA to be American propaganda. Even if that was the goal, we would make an effort to resist.”

At the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) awards ceremony in June, WHYNOT won two awards, adding to its count. A report about detained Chinese journalists Wang Jianbing (王建兵) and Huang Xueqin (黃雪琴) won the award for excellence in human rights reporting, while a series on the 35th anniversary of the June 4th Incident won first prize in news innovation. Because the editorial department had long since ceased operations, however, no one appeared that day to accept the awards in person.

Hsu Chia-Chi is a journalist focusing on political, cultural, and human rights issues in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. She previously worked for WHYNOT.

The Chinese-language version of this article was first published at Tian Jian.