Taiwan’s Vatican Gateway

At the beginning of this month, Taiwan’s ambassador to the Holy See, Anthony Chung-Yi Ho (賀忠義), had the chance to present his credentials to the newly chosen Pope Leo XIV in a ceremony that highlighted the Vatican’s ongoing diplomatic recognition of Taiwan. The occasion received typical coverage in Taiwan’s media — focused on diplomatic protocol and geopolitical implications while overlooking a deeper story about the country’s role as the Vatican’s Chinese-language communications hub.

For decades, Taiwan has quietly served as a bridge between the Vatican and Beijing — a story that rarely makes headlines but has shaped communications by the Catholic Church across the Taiwan Strait. Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been a space for the translation of Vatican documents and modernizing of liturgical practices, as well as facilitating religious exchanges with China. Catholics in Taiwan, numbering less than 300,000, have played an outsized role as the Vatican’s primary source for Chinese-language work and correspondence.

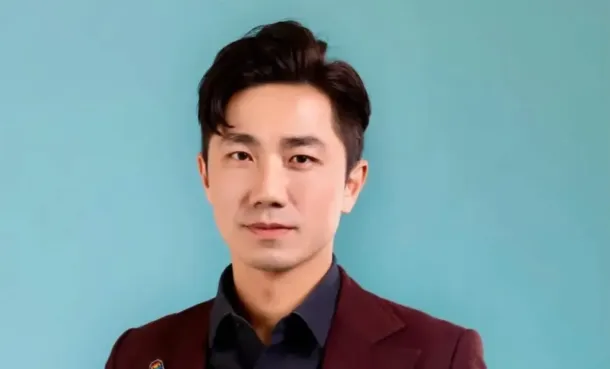

In this interview with Lingua Sinica, Thomas Tu (凃京威), a scholar of Vatican-Taiwan relations, explains how most journalists in Taiwan and beyond have approached Vatican stories related to the country purely through a simplifying geopolitical lens, viewing Taiwan’s relations with the Vatican as a diplomatic asset while a larger story looms behind — about the country as a Catholic communications hub.

Dalia Parete: From my understanding, the Vatican has had diplomatic relations with Taiwan since 1942, but they were downgraded in 1971. How would you characterize their relationship over the last decade?

Thomas Tu: First, we need to be precise about terms. This relationship was established between the Holy See and the Republic of China – specifically with Chiang Kai-shek’s Chongqing government in October 1942. Taiwan was still a Japanese colony at the time.

This is important because earlier in 1942, Japan had established ties with the Holy See. By choosing the Chongqing government over the Japanese-backed Nanjing government, the Vatican was essentially supporting China’s resistance. They even rejected Japan’s request to recognize Manchuria.

In 1971, when the Republic of China was expelled from the UN, most countries severed ties with Taiwan, including the United States, which eventually followed suit in 1979. The Vatican followed suit. They couldn’t be the only significant power maintaining full relations. Their Apostolic Nuncio [a papal envoy who serves as the Vatican’s official representative to a nation or international body] left for Bangladesh in 1971. Since 1972, they’ve maintained a chargé d’affaires [essentially a deputy] instead of a Nuncio.

However, compared to other states that completely cut diplomatic ties, the Vatican sustained the relationship. That’s their unique diplomatic approach.

DP: What changes have occurred under Pope Francis’s papacy (2013-2025) regarding Taiwan-Vatican relations?

TT: When it comes to Taiwan, I think what’s changed most is how things appear on the surface — not the Vatican representatives or the actual content or beliefs, but how they act in public.

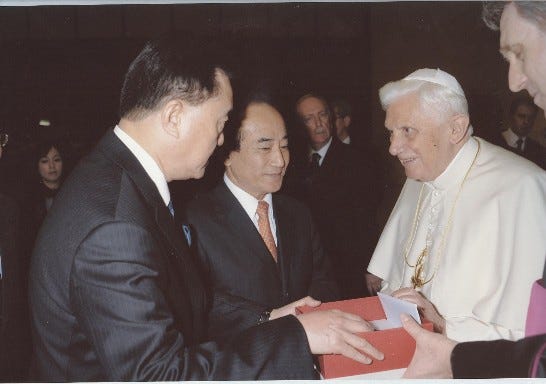

There have been various attempts under recent papacies to find ways to engage with and be informed about China. In fact, the Vatican has been seeking to establish contact with China for a long time, dating back to the 1980s. Every Pope since John Paul II’s election in 1978 has sought engagement with China, but Francis has pursued this goal more openly and transparently than his predecessors. Benedict XVI also worked toward improved relations with China, establishing a high-level China Commission in 2007 to compensate for his own limited knowledge of the country as a German diocesan priest by drawing on advisors with Chinese experience.

Pope Francis canceled that council because he’s a Jesuit, and they already have many members in China. [NOTE: Jesuits are members of a Catholic religious order founded in 1540, known for education, missionary work, and intellectual scholarship.]

Every Pope since John Paul II’s election in 1978 has sought engagement with China, but Francis has pursued this goal more openly and transparently than his predecessors.

The Jesuits possess unparalleled expertise in China relations, rooted in over 400 years of continuous engagement dating back to Matteo Ricci’s arrival in Beijing in 1601. Unlike other Catholic orders, Jesuits developed a uniquely sophisticated approach to China: they mastered the Chinese language, adopted Confucian scholar customs, and strategically cultivated relationships with emperors and the educated elite rather than pursuing direct popular evangelization.

The Jesuits possess unparalleled expertise in China relations, rooted in over 400 years of continuous engagement dating back to Matteo Ricci’s arrival in Beijing in 1601. Unlike other Catholic orders, Jesuits developed a uniquely sophisticated approach to China: they mastered the Chinese language, adopted Confucian scholar customs, and strategically cultivated relationships with emperors and the educated elite rather than pursuing direct popular evangelization.

Today, they maintain this expertise through direct presence and even run an independent center called “Beijing Center,” which is the primary Jesuit China study center today, founded in 1998 by Ron Anton, S.J.

DP: Taiwan has virtually no economic ties with the Vatican, with only minimal trade occurring during the pandemic in 2021. How does this relationship serve Taiwan’s broader interests, and what does it symbolize for Taiwan’s international legitimacy?

TT: If you ask other scholars, they will say that Taiwan still has 12 diplomatic allies in the world, most of which are Catholic countries — especially in Latin America. But those scholars — they’re not Catholic themselves — argue that if we lose the Vatican, then we will lose our diplomatic relations with those South American countries because they will follow the Vatican’s decision. But I don’t think that’s entirely reasonable.

From a diplomatic perspective, Taiwan can play two distinct roles. First, it can be a significant actor in inter-religious dialogue. We have a diverse range of religions here. Many, including some emerging faiths whose beliefs we haven’t fully grasped. However, we still allow them to exist, and we do not impose government restrictions on personal beliefs. We respect that freedom.

For example, our embassy to the Holy See has introduced groups like Fo Guang Shan (佛光山), an international Buddhist organization, and even showed Pope Francis a statue of the sea goddess Mazu (媽祖). Although inter-religious dialogue remains a marginal issue for the Vatican — whose main focus is liturgy, bishops, church governance, and church teaching — we can play a meaningful role in this Vatican initiative.

Second, Taiwan maintains its role as a bridge between the Vatican and China through the international priests, who can travel back and forth between Taiwan and China. Most of the international priests here in Taiwan have residency, but they are not citizens of Taiwan. So they can easily travel to China using foreign passports.

DP: So Taiwan has played a crucial communication role?

Yes. Since the 1980s, the Vatican has requested our assistance in bringing Vatican materials to China and translating them into Mandarin. This arrangement has deep historical roots. In the 1980s, Pope John Paul II asked the Taiwanese Catholic Church to serve as a conduit for bringing Vatican II reforms into China. The Vatican designated us as a bridge because we are a free country that Rome could easily contact. During this period, when China had just opened its doors slightly to the world, the Vatican needed us to translate materials into Mandarin and transport them into China. This actually goes back to the 1970s.

Even into the 1990s, some parishes in China were still using Latin for their liturgy, so Taiwan played a crucial role in modernizing Chinese Catholic practices. Taiwanese and Hong Kong priests collaboratively recorded videos about new liturgical practices and brought these materials through Hong Kong into China.

However, this role is limited to church issues, not international politics. Frankly speaking, the Vatican doesn’t consider Taiwan powerful enough to affect world affairs. We simply don’t have the capacity to help the Vatican manage relationships between major powers like Pakistan and India, or Palestine and Israel. Since the 1980s and 1990s, Taiwan’s role has been specifically focused on church relations between China and the Vatican.

Interestingly, our own government doesn’t really pay much attention to the Catholic Church here. It’s quite small and more complicated to manage compared to other religions like Buddhism or Protestantism. This bridging role wasn’t Taiwan’s choice; it was decided by the Vatican, making us an unwitting but essential link in Vatican-China relations.

DP: Given China’s sensitivity about foreign influence in its domestic affairs, even regarding religion, isn’t this role that Taiwan plays — with Taiwanese priests traveling to China and bringing Vatican materials — seen as foreign interference by Beijing?

TT: After the Chinese Communist Party released [a manifesto known as] Document No. 19 in 1982, officially granting some religious freedom (宗教信仰自由), this assistance was never considered foreign interference. But under Xi Jinping, we’ve seen these freedoms significantly restricted. In Taiwan, we are highly suspicious of China’s current attitude toward religion. Xi often speaks about returning to the glory of the 1950s. We’re concerned China might revert to that era’s level of religious control.

DP: Do Taiwan’s media and government emphasize the Catholic-based, value-based nature of their relationship with the Vatican to domestic and international audiences?

TT: No, they don’t emphasize anything specifically Catholic. The government just uses the same generic language they use for all relationships — like with the United States. They say something like: “We’re a democratic country, a value-based country, a religiously free country. We respect every religion and everyone in Taiwan can practice freely.”

This bridging role wasn’t Taiwan’s choice; it was decided by the Vatican, making us an unwitting but essential link in Vatican-China relations.

It’s basically just a comparison with China. They’re saying: Look, we are not like China, Taiwan has religious freedom, so the Vatican should not abandon us for China. But there’s nothing specifically about Catholic values or the Catholic Church.

DP: How seriously does the Taiwanese government take its relationship with the Vatican?

TT: The relations between the Holy See and Taiwan are stable without dramatic changes. Despite efforts to improve relations with China, the Vatican maintains its contact and collaboration with Taiwan. For instance, the Holy See sent Archbishop Charles John Brown and Cardinal John Tong Hon as Papal Representatives to Taiwan in 2024 to greet President Lai’s inauguration and the 5th Taiwan National Eucharistic Congress.

However, the Taiwanese government takes the relationship in more of a geo-political gesture. The Europe-Taiwan relations have thrived in recent years. Particularly, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Great Britain, France, and Italy are the most critical diplomatic targets for the Taiwanese government. Yet, the efforts for these “new friends” have not been equitably applied to the Holy See. The government’s lack of serious attention is evident in staffing. The MOFA’s South European section needs to cover France, Italy, Greece, and the Vatican within limited staff numbers. They put most of their effort into France and Italy, with only a few young diplomats covering Vatican issues. It may be because of the tiny territory and the lack of economic opportunities of the Holy See.

We are also experiencing a lack of Catholic diplomats in the government. Now our current Ambassador to the Holy See is actually Catholic — his whole family is Catholic. His personal belief gives him an advantage when reaching out to the Dicastery and Congregations of the Holy See. However, not every Taiwan Ambassador and diplomat to the Holy See has been Catholic.

DP: Do you think Taiwanese media are interested in Vatican-related news?

TT: They’re interested in major stories. You know, big issues. Like when late Pope Francis was appointed, everyone was asking, “Who is Pope Francis?” and “Why is he important?” However, many people are interested in the relationship between the Holy See and China.

DP: That was my follow-up question. When they do cover it, is the coverage more political or more from a Catholic religious perspective?

TT: It’s all about politics. Even when I was interviewed last month to discuss the election of the new Pope, my experience was that they don’t really want to spend much time on religion.

It’s all about politics (…) [The] media does not want to spend much time talking about religion.

First of all, the journalists themselves aren’t Catholic. Second, they need to consider their audience. Most of their viewers aren’t Catholics either. They don’t want to give a platform to preach religion, and I respect that. Our news media is quite neutral because we have different religions here.

DP: I looked at some data and Taiwan has fewer than 300,000 Catholics. Coming from Italy, of course that seems a pretty small community. What kind of sources do Taiwanese Catholics rely on for Vatican news? Are they English-based like Vatican news services, or do you have Catholic Chinese-language newspapers in Taiwan?

TT: First, from the Vatican itself, we have Vatican News in Chinese — the traditional Chinese version. But they only select some content from the Italian version, not everything.

We also have Vatican Radio in Chinese. They have Taiwanese priests or Hong Kong priests providing the Chinese service and translation. But even though we call them “Taiwan priests,” they weren’t actually born in Taiwan. They’re Malaysian or Indonesian, but they’ve served in Taiwan for several years before being sent to the Vatican for radio service. Most of them are originally from Southeast Asia, though some are from Hong Kong.

DP: What about local sources?

TT: For Taiwan, we have one religious newspaper, the Catholic Weekly (天主教周報). It is issued by the Taipei Archdiocese and covers Catholic Church issues across all of Taiwan every week.

Every diocese also has its own diocesan newspaper — weekly or monthly. But those newspapers focus more on church issues. We also have Radio Veritas (天主教真理電台). It was established in Manila, but we have a branch in Taipei covering Chinese news media. They have a YouTube channel, where they upload new content, such as daily mass, to attract more viewers.

DP: Can I ask you about the content of the Catholic newspapers? The ones in Italy are very conservative. You mentioned these are very religion-based. What topics do they cover?

TT: Still pretty traditional stuff. Family values, some social issues, personal religious reflections, and announcements, like when a priest gets hired somewhere, or exchanges, or pastoral letters to the world.

They translate Vatican documents into Chinese and publish them. And I need to mention something very important: now the formal documents, like the Pope’s letters to the world, are translated by Taipei. Not by Hong Kong, not by China, but by Taipei.

DP: When did this start?

TT: I think it’s been at least 10 years. Actually, probably longer than that. All the first-hand translations are done in traditional Chinese here in Taipei. Then I imagine they probably convert that traditional Chinese into simplified Chinese and send it to China. But all the original translation work is done in Taipei first. It’s a role Taiwan has played that few people are even aware of.

Thomas Ching-wei Tu is a doctoral fellow at National Chengchi University in Taiwan, researching the intersection of religion and international relations. Before pursuing his PhD, he spent nearly a decade in Taiwan’s government and public service think tanks, specializing in diplomacy, economic cooperation, and trade policy, including Taiwan’s participation in the WTO and APEC. His current research focuses on Vatican diplomacy.