Redacting History

Monday this week marked the 17th anniversary of the Wenchuan earthquake, a 7.9 magnitude tremor that devastated Sichuan province and tragically took the lives of nearly 100,000 people. On the anniversary this year, one particular Wenchuan-related item surged to the top of search engine Baidu and hot search lists on the social media forum Weibo. It involved a vox pops interview given on location one week after the 2008 quake by Li Xiaomeng (李小萌), a reporter from state broadcaster CCTV. In the old broadcast shared on social media on May 12, Li comes across a farmer known simply as “Uncle Zhu” (朱大爷) as she strolls along a collapsed mountain road. Speaking a local dialect, Zhu stoically tells the journalist about the appalling conditions in the area. Through an interpreter he explains to the reporter that he is returning home to harvest his rapeseed crops in order to “reduce the burden on the government” — meaning that he will have some income and not need to be totally dependent on aid. By the end of the interview the farmer is convulsed with sobs, the tragedy of the situation coming through.

Li posted this week on Weibo to commemorate the moment, revealing that Uncle Zhu passed away in 2011. She said: “That conversation, with its unexpected, banal but heartbreaking details, showed all of us in China that people like Uncle Zhu, with their calm acceptance in the face of catastrophe, have the backbone to do what is right.” Other media, including China Youth Daily, an outlet under the Communist Youth League, built on Li’s exchanges with the Uncle Zhu in the years after the quake to commemorate the anniversary.

But a key portion of the television exchange was edited out of this year’s commemorative coverage. Near the midpoint of the original video, Li turns from her conversation with Zhu to interview several other farmers. One farmer explains that his child was killed in the earthquake, “buried in Beichuan First Middle School.” This exchange referenced the widespread collapse in the quake zone of shoddily constructed school buildings, resulting in the death of thousands of children. Revelations of school collapses briefly drove a wave of public anger, and a burst of Chinese media coverage — before the authorities came down hard.

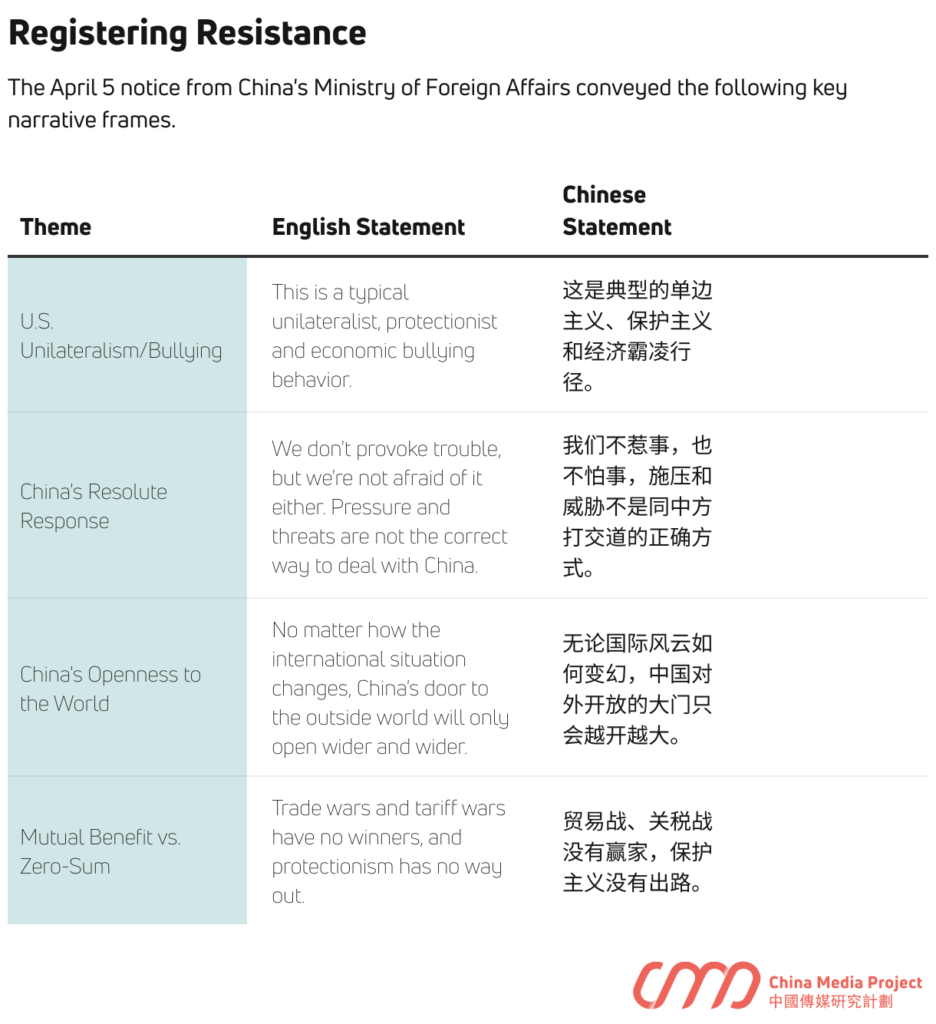

As Dalia Parete wrote last week for CMP, Chinese media are generally subject to strict controls when reporting on breaking disaster stories. but past disasters too are subject to careful narrative control, with inconvenient facts often erased from official memory.